Continuing on the theme of value stream mapping (and process mapping in general) from my article “Where is your value stream map?”, I outlined the typical scenario: The map is built by the continuous improvement team, and they are the ones primarily engaged in the conversations about how to close the gap between the current state and the future state.

Ah, here’s the rub. For some reason, managers have a reluctance (or even disdain) to talk about operations, preferring to keep conversations in financial terms of cost, earned hours, yield, and the like. These are all outcomes, but they are outcomes of process. It’s only by changing the process that those outcomes can sustainably change.

None of this addressed the past-due issue. In fact, this made it worse, because when a shop is behind, the management reflexes are to 1) increase batch sizes and 2) expedite.

Likewise, I’ve seen a lot of cases where the people primarily participating in building the value stream map were working-level team members. Yes, it’s absolutely necessary to have their insights into how things really are for people trying to get stuff done. Yes, it’s critically helpful for them to understand the bigger-picture context of what they do. However, all too often, I see senior leaders disengaged under the justification that they are “empowering” their workers.

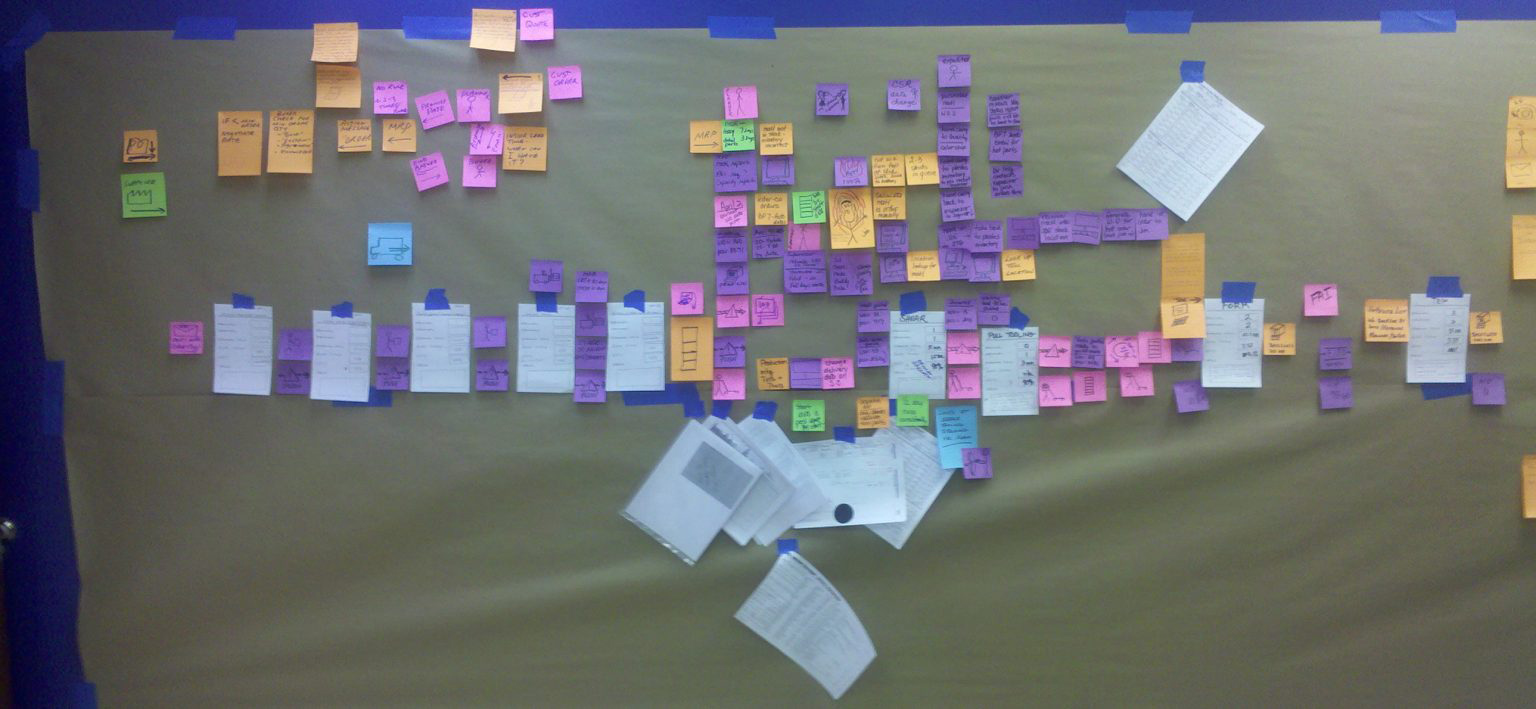

There is an icon in the middle of the map. Here is a close-up.

|

So please consider turning off your ad blocker for our site.

But this role made him the gatekeeper. So the customer service people (you can see their names in the lower left corner) would be pressuring Jim to jump their hot orders (and they were all hot by the time it got to the point where there was paperwork release, which is another story) into the queue so they could tell their customers that their orders were “in production.”

The current performance is an outcome of the current system. People do their best within the system they have to work within, and we have to assume the system reflects management’s understanding of how things should operate to get the best results.

Now we start to see the organic intersection between Toyota kata and the value stream map.

It also resulted in a staged order queue (materials and paperwork on carts) that snaked through the shop until it finally (days later) got to the actual production cell that, once they started, could actually knock things out pretty fast.

It isn’t about seeing what you could do by removing waste. It isn’t “What could we improve?” It’s “What must we change to reach our objective?” Again, this is a management function. It’s called “leadership.”

Establishing focus is a leadership and management task. It doesn’t work to just say, “We need to improve,” or even worse, “We need to get lean.”

Just to be clear: We absolutely want to create conversations about improvement at the level of the organization where value and the customer’s experience are actually created. The point here is that those conversations can’t be the exclusive domain of the working levels. It is critical for line leadership to be, well, leading. They can’t just delegate this to the continuous improvement specialists. Nor can they simply leave it to the working levels to sort it out—not if they expect it to work for any length of time.

Who reports on progress?

The purpose of mapping a future state is to design process flow that you believe will meet your challenge if you can get the system to work that way.

We want to solve problems at the lowest possible level, but no lower. In this working example, asking the shop floor workforce to fix this problem would be futile. Yes, they can propose a different structure, but they don’t control how orders are released, they don’t control how capacity is managed, and they don’t control the account managers who are fighting for a spot in the queue. The workers had been complaining about this bind for a long time. It wasn’t until the people running the business saw how the overall system worked that they understood it was a systemic issue, and “the system” belonged to line management.

The key question for this team was “Who needs to have what conversation about work priorities so it isn’t all on an hourly associate to decide which customers will be disappointed?”

Who needs to fix this?

What the future-state value stream map does (or should be used to do) is translate those business objectives into operational requirements for the process.

What is your target condition?

That conversation about progress I talked about above? That can’t be solely about the performance. It has to be about what is changing in the way the work is being done, and more important, what is being learned.

The cool thing here is that you really can’t get this wrong. If you set a goal of radically improving your performance on any single aspect of your operation, you’ll end up improving pretty much everything during the process of reaching that goal. But it’s critically important to have a goal to strive for. Otherwise, people are just trying to “improve” without any objective.

Those problems (or obstacles, in Toyota kata terms) at the value stream level become challenges (again in Toyota kata terms) for the respective process owners.

Sometimes these things are obvious frustrations to managers. But often they are overwhelmed with general performance issues, or trying to define problems in terms of financials. That is an opportunity to focus on the kind of performance that would address the financials.

Published: Wednesday, February 21, 2024 – 12:01