So please consider turning off your ad blocker for our site.

To meet that need, NIST scientists have devised the Kibble Dynamic Force Reference (KDFR), a traceable, dynamic force source based on the same principle used in a Kibble balance to generate an exactly known static force to counterbalance the weight of an unknown mass.

However, someone has to pay for this content. And that’s where advertising comes in. Most people consider ads a nuisance, but they do serve a useful function besides allowing media companies to stay afloat. They keep you aware of new products and services relevant to your industry. All ads in Quality Digest apply directly to products and services that most of our readers need. You won’t see automobile or health supplement ads.

Dynamic system models accounting for these effects are sometimes used to try to compensate for them. But they are generally of limited accuracy and often require measurements from additional sensors.

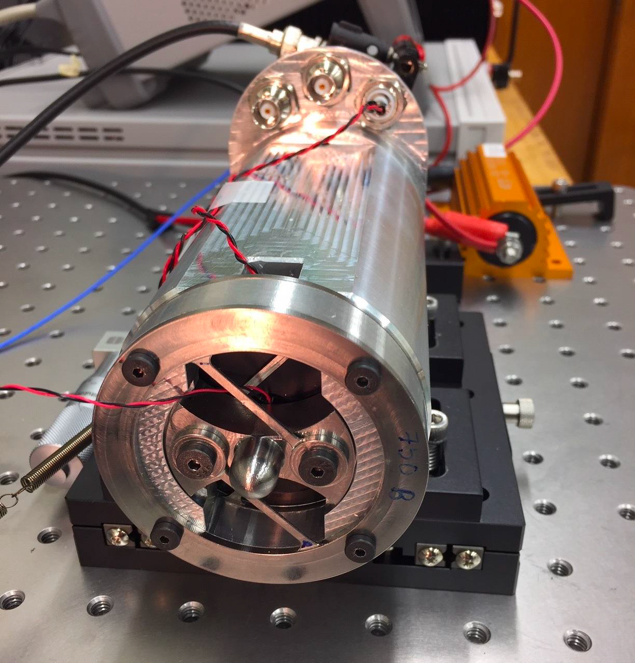

The Kibble Dynamic Force Reference (KDFR) transmits an accurate and traceable dynamic force to a structure or sensor under test. The device essentially consists of a hollow cylinder magnet surrounded by a wire coil attached to an armature. When a current is run through the coil, it creates an electromagnetic force that pushes the armature forward, transferring a dynamic force to any external structure in contact with the armature. The response to the dynamic force reveals properties of the structure. Credit: Sean Kelley/NIST

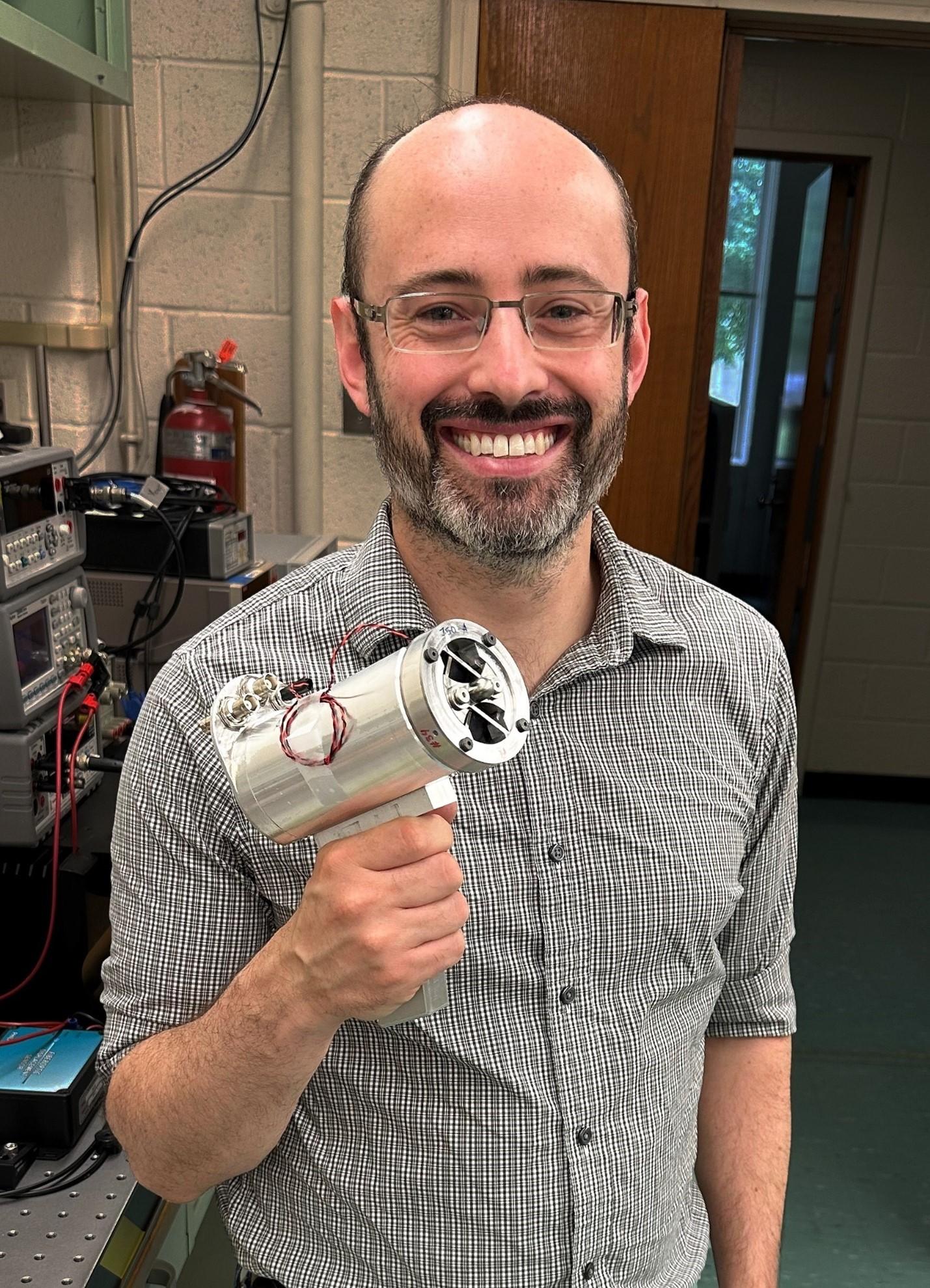

NIST researcher Jared Strait with a prototype hand-held KDFR. Credit: NIST

“Separating the current and voltage measurements into two steps requires a high degree of uniformity and stability of the magnetic field, which is difficult to achieve in a dynamic measurement,” Chijioke says. “Therefore, in the KDFR, the current, voltage, and velocity are all measured simultaneously and synchronously at a rapid sampling rate (tens of kHz), providing the generated force output at each instant of time.”

“Knowing the force accurately is required when you want an accurate measurement of frequency response of the structurer rather than just knowing its resonant frequencies,” Chijioke says. (Frequency response is the ratio of motion-to-force input as a function of frequency.)

The Kibble principle allows accurate determination of the mechanical force generated by a current flowing in a wire that moves in a magnetic field.

“The KDFR could be used, for example, to determine how much of an input force a support structure would transmit to what it is supporting, to infer from measurements of strains and deformations on an aircraft surface in flight what forces were acting on the aircraft, and of course to calibrate the dynamic response of a force sensor,” he says.

Kibble technology

Accurate measurements can, however, be achieved if the sensor systems are calibrated both dynamically and, importantly, as assembled for the measurement, rather than relying on an off-site calibration of the force sensor in a standards laboratory.

In contrast, the KDFR can be driven to produce a variety of force-output wave profiles. Sinusoids and frequency sweeps (known as “chirps”) are particularly well-suited for measuring frequency response amplitude and phase with high resolution.

Prototype KDFR device mounted on laboratory bench for testing. Credit: NIST

In addition, measurements focused on behavior at specific frequencies can be challenging. These require the ability to excite the structure at the specific frequency of interest, together with an accurate measurement of the exciting force. Existing techniques do not combine these two aspects very well.

Measurements of dynamic force generally do not correspond to those obtained by a statically calibrated force sensor. That difference results because of the inertia of system components that accelerate in the presence of the dynamic force, and also because of the frictional (i.e., damping) forces that moving material experiences.

In a mass-measuring Kibble balance, accurate measurements require two steps. In one, the current is adjusted to generate a force that exactly offsets the static force exerted by an unknown mass, with the coil stationary. In a separate step, the coil is moved with no current flowing through it, and the voltage generated between its ends is measured.

Quality Digest does not charge readers for its content. We believe that industry news is important for you to do your job, and Quality Digest supports businesses of all types.

However, testing for dynamic force—such as automobile crash testing, fatigue testing of materials, and the changing forces applied during machining—has traditionally been difficult to measure because dynamic force changes continuously as it is applied. In many applications, a time-varying force causes large errors in instruments calibrated to measure static force. It is thus necessary to calibrate the response of these instruments to dynamic forces.

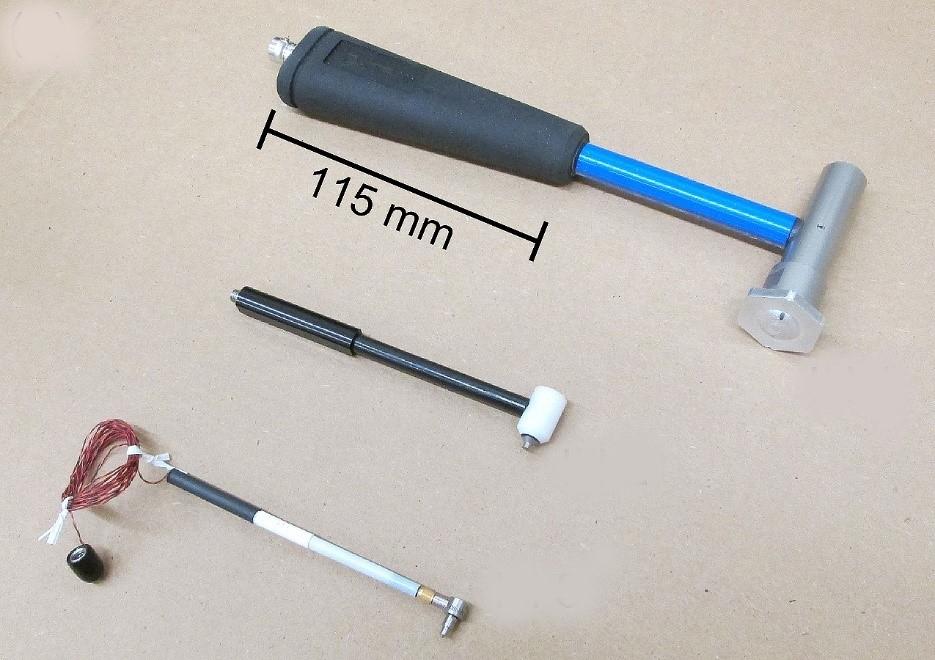

When using impact hammers, the fact that the output force is a single pulse is a strong limitation in determining system frequency responses.

Existing methods for generating known dynamic forces for calibrations and other applications commonly use a calibrated force sensor that detects an electrical signal, such as a rise in voltage or change in resistance, in response to the applied force. They are not primary devices and require periodic recalibration.

Measuring vibrational resonance frequencies is important, for example, to avoid exciting them in an airplane structure that could shake itself until damaged, or as a method of measuring material elastic properties. But it is not necessary to know the force accurately in order to measure the resonant frequencies.

Our PROMISE: Quality Digest only displays static ads that never overlay or cover up content. They never get in your way. They are there for you to read, or not.

Innovation

Measuring Up: Kibble Dynamic Force Reference

A primary standard for testing structures and calibrating force sensor systems

By contrast, the patented KDFR generates waves or pulses of repeated dynamic force. “There is noise—incidental measured output that is not related to the force applied—in any kind of dynamic measurement,” co-inventor Ako Chijioke says. “As a result, many repeated pulses are generally required to obtain a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio.”

Various impact hammers with electrical connections. Credit: NIST

First published July 18, 2023, in NIST News.

“Knowing the frequency response,” Chijioke says, “reveals the stiffness of structures and elastic constants of the material, its damping coefficients, the number of lumped elements or degrees of freedom needed to model the structure to a desired degree of fidelity, and the presence of nonlinear response of the structure, to name a few.”

It is expected to be used for applications such as structural testing (including modal testing, which identifies the natural vibration modes of an object) of vehicles, buildings, and bridges as well as for calibrating force sensor systems used to measure dynamic forces, such as in materials testing (dynamic tensile testing, fatigue testing, impact testing), and in aerodynamic balances in wind tunnel tests.

Thanks,

Quality Digest